Lakeport Legacies · Rev. Green Hill Jones: From Slavery to the State House · Blake Wintory (Lakeport Plantation)

Rev. Green Hill Jones: From Slavery to the State House

presented by

Blake Wintory (Lakeport Plantation)

Thursday, April 26

Refreshments & Conversation @ 5:30 pm

Program @ 6:00 pm

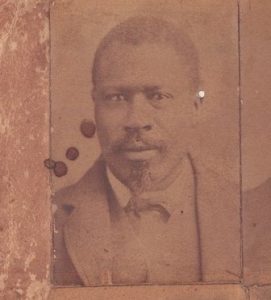

Rev. G. H. Jones served in the Arkansas General Assembly in 1885 and 1889. Courtesy of the Old State House Museum.

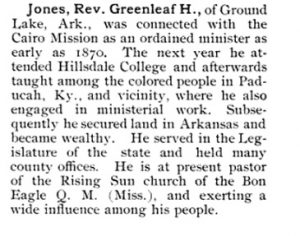

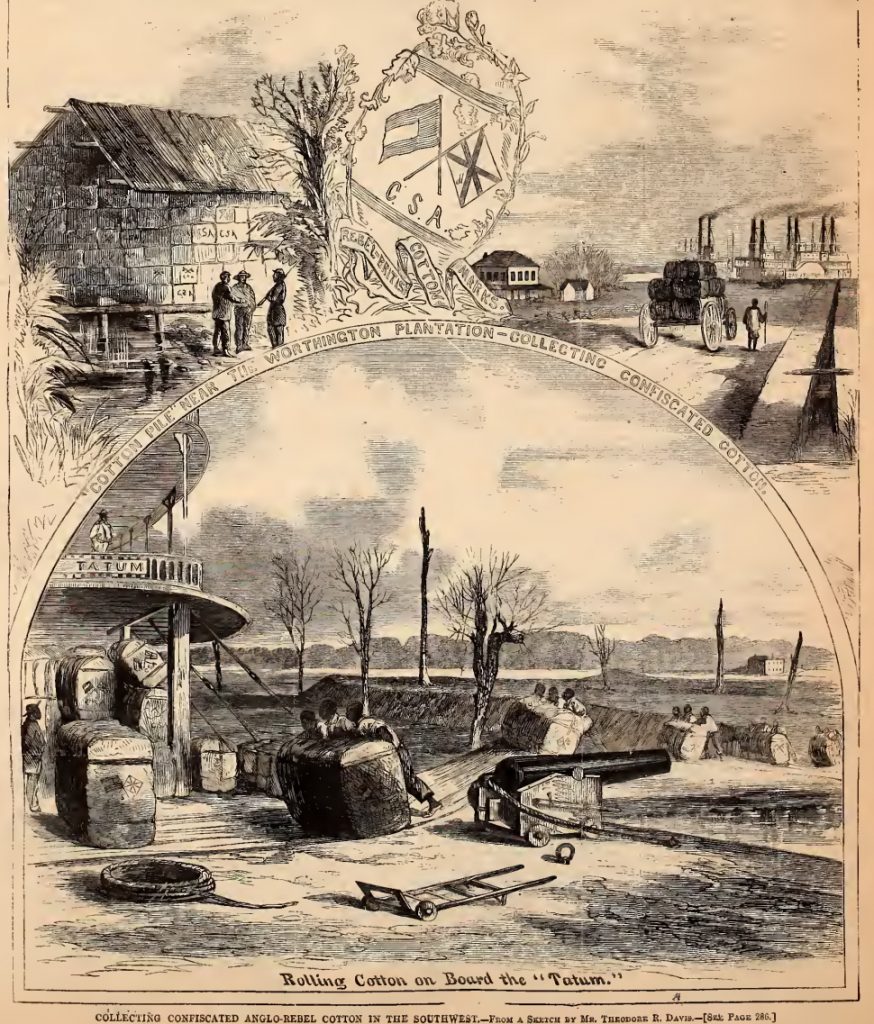

Rev. Green Hill Jones was one of over a dozen African-American men from southeast Arkansas who served in the Arkansas General Assembly between 1868 and 1893. Born a slave in Maury County, Tennessee in 1842, Jones was brought four years later to Kenneth Rayner’s Grand Lake cotton plantation in Chicot County, Arkansas. A young man when the Civil War began, Jones joined the Union Army at Memphis in 1863. After the Civil War, he became an ordained minister and received an education in the North. He returned to Chicot County in 1873 and was soon elected county treasurer (1874-1876), county assessor (1876-1878), and to two terms in the Arkansas House (1885, 1889).

Wintory will tell his story from church and school records, and interviews with Jones and others contained in his Civil War-era pension file.

Wintory’s talk is based on his research on Jones and Arkansas’s eighty-six other 19th century African-American legislators. His essay on the subject will be published in May 2018 in A Confused and Confusing Affair: Arkansas and Reconstruction. Edited by Mark Christ, the book will be published by Butler Center Books, a project of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library System.

Register for this FREE Event

(by phone, email or online)

870.265.6031 ·

601 Hwy 142 · Lake Village, AR 71653