Washington County Courthouse’s Mysterious Belfry

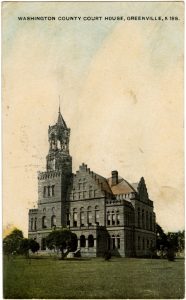

Washington County Courthouse, Greenville, Miss., built 1890-91, is pictured here around 1900. The bell tower was most likely reduced in the early 1930s. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Last year, I heard an odd story: the Washington County Courthouse’s belfry tower was originally a “hanging tower” used to hang convicted criminals. The sources were adamant but could only say they had heard it from others.

My first instinct was this was recent bunk history–people seeing an unfamiliar and altered architectural feature and drawing a wild conclusion. For a building built in 1891, this is not ancient history. If the courthouse’s tower was really a “hanging tower”–a gruesome public spectacle–there should be amble written evidence.

After researching the problem, my initial instincts proved to be correct. Newspapers from the early 20th century describe executions in the yard of the county jail behind the courthouse….and NOT in the courthouse itself. However, I was a little surprised to find one source that did describe an execution in the tower. I’ll examine that later, but first some background on the courthouse and jail

In January 1890, the Mississippi Legislature authorized the Washington County Board of Supervisors to issue bonds, not to exceed $100,000, to build a new courthouse and jail. In July, the Board selected plans for a courthouse prepared by the McDonald Brothers of Louisville, Kentucky. Meanwhile, the Board selected jail plans submitted by L. T. Noyes, an “agent for the Diebold Safe and Lock Company” (Board of Supervisor Minutes, July 12, 1890). Initially, Charles Dollman of Memphis was selected to build the courthouse and John F. Barnes of Greenville to construct the jail. Barnes would ultimately build both.

The McDonald Brothers’ plans called for an 80 x 100 foot, two-story high building including “a tower about 180 feet high with an open bell niche” (Greenville Times, July 19, 1890). We now call the courthouse’s architecture, popularized by Henry Hobson Richardson, Richardsonian Romanesque. Washington County’s courthouse is one of only two in this style in Mississippi. It also has a striking resemblance to another McDonald Brothers’ project, the 1888 Washington County Courthouse in Salem, Indiana. Today, the courthouse still has an impressive tower, but the bell niche or belfry was likely removed in 1930 when Jackson, Mississipi architect James M. Spain remodeled the building.

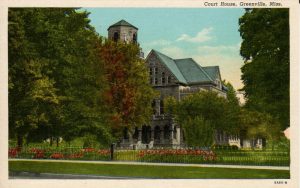

Washington County’s Courthouse, ca 1940, with the tower lowered and belfry removed. Unseen is the 1891 jail behind the building. Lakeport Plantation Collection.

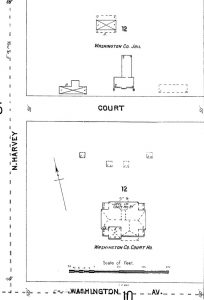

Added to the National Register in 2014, the Washington County Courthouse is impressive public architecture to be marveled over. In contrast, the 1891 jail is, at most, an afterthought. The jail appears in Sanborn maps, but 20th-century images of the courthouse give no indication of a jail lurking behind it. [Note: there are at least two 1890s images that show the jail, they are published in Washington County, Mississippi]. In 1950, a new jail was constructed north of the 1930 Annex and, it seems, the original jail was erased from the public’s imagination.

This brings me to a 1990 article published in the Delta Democrat-Times. The article celebrates the 100th anniversary of the courthouse and coaxes the building to tell its stories through oral histories housed at the Percy Library. The author tells us several of the interviews “spoke of hangings at the Courthouse,” but “they were not viewed by the public.” However, the author cites a 1977 interview with Lille B. Parker that does mention a hanging in the courthouse. Parker attended the execution of Eddie B. Weeks on the morning of May 12, 1932 and believed it to be the last in Washington County. “They hung him down where the Court House is at, up there where a big old clock used to be,” she stated in the interview. She continued, “they was boards up there, two by fours or something—you could see it a long time. They done tore it down now.”

Not to disparage Mrs. Parker and her memory, but her account is not supported by the written accounts of Weeks’ execution in 1932.

The DDT on May 10, 1932 wrote, “The gallows have been completed for several weeks and are located in the rear of the Washington County jail.” Two days later the paper reported, “Eddie B. Weeks…was hanged at Washington county jail here this morning…” Weeks walked “from his cell to the rear door of the county jail and ascend[ed] the stairs to the enclosed gallows that were to take him to his death….Near a thousand members of Weeks[‘] race gathered around the jail yard on all sides.”

Parker’s memory is also in conflict with a 1978 interview not mentioned in the 1990 DDT article. Leonard Brown is a solid source. He was born in 1896 and, according to the U. S. Census, was a janitor at the courthouse in 1930. In the interview, Brown recalled his duties as a cook, groundskeeper, and transporting prisoners to Jackson. When asked about hangings at the jail, he described what is most likely the 1932 execution of Weeks:

“Well, I never witnessed but one…they built a scaffold right out in the corner of the jail…the day of the hanging we wanted to go in where we could see it, but they wouldn’t let us go in. We had to stand out…we could see that afterwards…”

Earlier accounts in the Greenville Times support Brown’s memory of executions at gallows constructed in the now forgotten jail yard:

- 1907 — private hanging — “took place in an enclosure on the west side of the county jail” — Greenville Times, Feb 16, 1907

- 1908 — public hanging — “paid the penalty for his brutal crime on the gallows at the county jail” — Greenville Times, Feb 23, 1908

- 1909 — public hanging — “paid the penalty with his life on the gallows…He was led onto the scaffold in the jail yard….” Greenville Times., August 21, 1909

The primary sources clearly debunk the story of the “hanging tower” at the 1891 Washington County Courthouse. While it is debunked, the story very likely has more depth than I initially anticipated. The rumors, perhaps, came to life in 1932 as Weeks’ execution intersected with the courthouse’s remodel. Accounts of the 1930 remodel by architect J. M. Spain don’t specifically mention work on the tower, however, the DDT, Dec 27, 1929, stated, “the upper floor would be repaired [and] new plans will take in the upper floor of the structure.” Mrs. Parker’s recollection seems to mention work being done on the tower in 1932: “they was boards up there, two by fours or something—you could see it a long time. They done tore it down now.”

Mrs. Parker was one of nearly a “thousand people” gathered at the courthouse and jail that morning. Many of them, unable to see the jail yard execution in the enclosed gallows, looked up at the boxed-in tower and assumed the execution was taking place in that public, yet obfuscated spot. With the original jail replaced in 1950 and the yard paved over, the only place for people to attach memories and stories of the 1932 hanging is the mysterious and altered tower.

While people love a mystery or “hidden secrets,” there is no good reason to keep telling the story of the “hanging tower.” It is just not true nor does it lead to deeper understanding of the history of the courthouse or Greenville. Primary sources like newspapers, oral histories, and county records tell us legal hangings in Washington County, from the early 1900s through 1932, took place in gallows constructed in the jail yard behind the Washington County Courthouse.

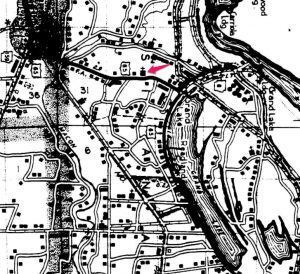

The real mystery is when exactly was the belfry removed. For such a public building, it is strange that historians and preservationists have not been able to pin down the exact date when the tower was lowered. Bill Gatlin’s 2014 National Register nomination states: “The tower was reduced from its original height in the 1930s, presumably during a renovation project led by architect James. M. Spain.” Local historian, Princella Nowell, makes the same case in an article published in Life in the Delta: [J. M. Spain’s] improvements [in 1930] included plumbing, heating and wiring. He may have been responsible for removing the bell tower.”

This 1927 flood photograph shows the Washington Courthouse’s tower still intact (left-hand corner). Courtesy of Princella W. Nowell.

The lowering of the tower can be narrowed down to around 1930 when Spain led a renovation of the courthouse. Nowell has confirmed the tower was still intact in 1927, as one photograph from the 1927 flood shows. Newspaper reports of Spain’s 1930 renovations of the courthouse and the Board of Supervisors records are vague, but a 1929 article in the DDT (cited above) mentions the work “will take in the upper floor of the structure.” Mrs. Parker’s 1977 recollection of the events in May 1932 speaks of the tower being boarded up. Finally, photo postcards ca 1940 show the courthouse’s tower reduced.

It’s hard to believe that a major alteration to such a public building went unnoticed and largely uncommented upon. If you know of primary sources that mentions or shows a change to Washington County Courthouse’s tower, send an email to lakeport.ar@gmail.com.

Sources:

Brown, Leonard. Oral History Interview, September 20, 1978, Special Collections, Percy Library, Washington County Library System [also online at MDAH].

The Daily Democrat-Times, December 27, 1929; May 10, 12 1932.

Gatlin, William. Washington County Courthouse, National Register Nomination, 2014.

Greenville Times, February 22, July 19, 1890; February 16, 1907; February 23, 1908; August 21, 1909.

Hall, Russell S., Princella W. Nowell, and Stacy Childress. Washington County, Mississippi. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

Nowell, Princella W. Email and phone communications, April 17, 2017-February 26, 2018.

Nowell, Princella W. “Old Courthouses,” Life in the Delta [emailed to the author, February 7, 2018].

Ingram, Deborah, “If walls could only talk … Courthouse could share tales,” The Delta Democrat-Times, May 8, 1990, in “Courts,” Vertical File, Percy Library, Washington County Library System.

Parker, Lillie Belle. Oral History Interview, February 18, 1977, Special Collections, Percy Library, Washington County Library System [also online at MDAH].

Washington County Board of Supervisor Minutes, Book 4.

Washington County Court House, ca 1909

Thanks

Special thanks to Princella Nowell, Clinton Bagley, Bill Gatlin, Benjy Nelken, and the staff at the Percy Library for their help.