The Other Lycurgus Johnson: Exploring History at Lakeport

A version of this article originally appeared in Life In the Delta, August 2016

Amanda Worthington, living at the Willoughby Plantation at Wayside, lamented in her diary in 1862 that her invitation to Linnie Adams’ 15th birthday party had arrived a month late “after the thing was over and nearly forgotten.” With Linnie across the river at Lakeport in Chicot County, Arkansas communication between the two friends was cumbersome. The two did exchange timely letters during the Civil War, but after a visit to Lakeport in August 1865, Amanda confessed “I love Linnie so much – I do wish she lived on this side of the river.”

Amanda and Linnie would have marveled at the convenience of the two bridges that have connected Chicot County with Washington County since 1940. However, the counties have been connected for far longer. Many Washington County couples married in Chicot County at Point Chicot and later Columbia, since Washington County’s first county seats, Mexico and Princeton, were many miles down river from the county’s northern section. The practice ended when old Greenville, not too far from the current city, became the seat in 1846. Amanda Worthington and Linnie Adams’ friendship also testifies to the connection. The Worthingtons and Johnsons (Linnie’s mother was a Johnson) were some of the first planters in the region. They arrived from Kentucky in the 1820s and 1830s and ultimately built huge cotton plantations with hundreds of enslaved laborers at Leota, Lake Washington, Grand Lake, Sunnyside, and Lakeport.

Today the 1859 Lakeport Plantation is an Arkansas State University Heritage Site restored to capture and preserve the house and the history of the people who lived and labored there. Built with a view of the Mississippi River for Lycurgus and Lydia Johnson, guided tours of the house and exhibits explore 19th century life, the lives of enslaved laborers, and the preservation of the structure. While Lakeport is the locus of the history, it is not where the story ends. Lakeport explores the Delta through on-going research, publications, and our “Lakeport Legacies” lecture series.

Our 2016 Lakeport Legacies, which began in March, dug deep into the Delta’s history with presentations on the geology of the Mississippi Alluvial Valley, the life and family of African American politician James Worthington Mason, the lives of five Italian-American immigrant sisters, the Arkansas Delta’s Mid-Century Modern architecture, as well as the history of the Mississippi Capitol Building.

By the time this is published, Lakeport will have one presentation left in our 2016 Legacies series: “The Other Lycurgus Johnson: U.S. Colored Troops and Civil War Pension Files in the Delta” to be presented August 25 by Lakeport Director, Dr. Blake Wintory.

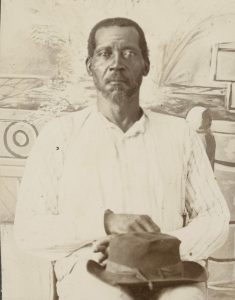

Pension files sometimes contain photographs of claimants, like this one of John Gordon who joined the 11th Louisiana Infantry in 1863. Gordon was a slave on George Falls plantation on Deer Creek in Washington County, MS. Linda Barnickel highlights this find in her book on Milliken’s Bend.

Beginning in 1863, the Union Army heavily recruited slaves into their ranks. Nearly 200,000 African American men served in the Union Army, with over 47,000 coming from Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The U.S. Pension Bureau, created in 1862, provided monthly payments for Union soldiers and their affected families disabled during the war. Later the criteria for a pension were expanded and by the mid-1890s, the Bureau accounted for over forty percent of the Federal budget. Today the National Archives holds about 100,000 pension applications for African Americans who served in the Union Army during the Civil War.

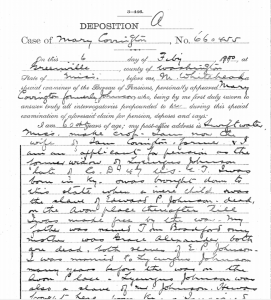

Challenged to prove their identity, African American pension claimants were often hindered by illiteracy and lack of documentation of important life events like marriages, birth, and even age. To fill the gaps, the Pension Bureau initiated “special examinations,” generating volumes of interviews with family, friends, comrades, and former owners. These examinations are a trove of information on 19th century African American life, sometimes providing complete life histories for former enslaved laborers who toiled on Delta’s plantations.

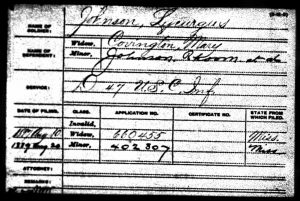

General index card for Lycurgus Johnson, Company D, 47th US Colored Infantry. General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. T288, 546 rolls (Accessed on Ancestry.com)

One pension that caught my attention is for a one Lycurgus Johnson. This Lycurgus, who happens to share the name of Lakeport’s owner, enlisted at Lake Providence, Louisiana on May 5, 1863 in the 8th Louisiana Regiment Infantry (African Descent), Company D–later renamed the 47th U.S. Colored Infantry. Sgt. Johnson died just over a year later on July 20, 1864 in Vicksburg of tuberculosis, then called “consumption.”

Lycurgus’ widow, Mary Johnson, remarried in 1880 and filed for a pension under her new name “Covington” with her two sons Rhoom and James Johnson. According to an interview with Mary in 1900, she and Lycurgus were slaves on Edward P. Johnson’s Avon Plantation on Lake Washington. (Edward Johnson and Lakeport’s Lycurgus were first cousins). She arrived on the plantation as a “mere child,” while Lycurgus arrived from Kentucky around 1849, when he was likely in his early 20s. He and Mary were married by “a slave-preacher [Hilliard Holmes] long before the war on the Avon Place & we lived together without separation till Lycurgus Johnson enlisted,” she recalled. Mary was a house servant and Lycurgus worked around the house; he’d “drive the wagon & did things that did not require heavy work” due to his illness.

Pension records like that of Lycurgus Johnson can provide important details about African American communities on the plantation. For example, the file also includes interviews with two other slaves on the Avon Plantation, Matt Harris and Downing Williams, and an affidavit signed by the slave preacher, Hilliard Holmes, that married the couple in 1850.

Mary also revealed Lycurgus has always been sick: “it was just the consumption that ailed him. He was just up & down all the time for several years

before he enlisted.” Questioned why the army enlisted a sick man she replied, “he wanted to go so bad because all the other colored people were going in the army.” The pension was eventually denied because Lycurgus’ illness was preexisting and his two surviving sons were both over sixteen. By 1900, James Johnson, appears to be the only surviving child of twelve. According to the census that year, he and his wife Eujean and two children were farming near Wayside.

Unfortunately, the pension file for Lycurgus Johnson leaves the basic questions about the origin and meaning of the name “Lycurgus,” unanswered. Pension files have their limitations, often focusing on a specific issue. In this case, Lycurgus Johnson’s pre-existing illness. When asked about Lycurgus’ parents’ health, she stated “I never knew Lycurgus Johnson’s father & mother or brothers or sisters & never heard what caused their deaths.” But perhaps she did know more about who they were. She must have been aware that her husband’s father was white. In 1864, when the couple had their marriage legalized by a military chaplain in Vicksburg, Lycurgus was recorded as a “quadroon” with a “white father.”

“Lycurgus” was a common name in the white Johnson family. Lakeport’s Lycurgus Johnson was born in 1818, the same year as Edward’s brother, Leonidas Lycurgus Johnson. Both men had grandsons that were there namesake. It was not uncommon for a house servant like Lycurgus (born around 1827) to be bestowed with an honorary family name.

The Delta certainly has a rich and intriguing history to be explored. History at the Lakeport Plantation opens up many topics, whether it is relationships with Washington County planters or a former slave named Lycurgus.

The Delta certainly has a rich and intriguing history to be explored. History at the Lakeport Plantation opens up many topics, whether it is relationships with Washington County planters or a former slave named Lycurgus. You can learn more at our next Lakeport Legacies, August 25 at 5:30 p.m or by touring Lakeport. Lakeport is open year around with tours scheduled at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. Monday through Friday or by appointment, 870-265-6031.

Dr. Blake Wintory has been the on-site director at the 1859 Lakeport Plantation since 2008. He is the recent author of Chicot County (2015) in Arcadia Publishing’s “Images of America” series. His wife, Debra, is Greenville’s Chamber Director. They have a five year-old daughter, Janey.

in 1936 as the “

in 1936 as the “