“A Weary Land” Book Signing with Dr. Kelly Houston Jones

Join us at the Lakeport Plantation Museum

for a book talk and signing on

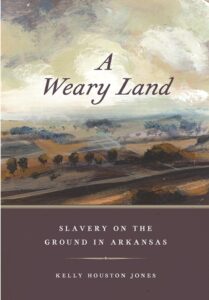

A Weary Land: Slavery on the Ground in Arkansas

with author Dr. Kelly Houston Jones

Saturday, September 16, 2023.

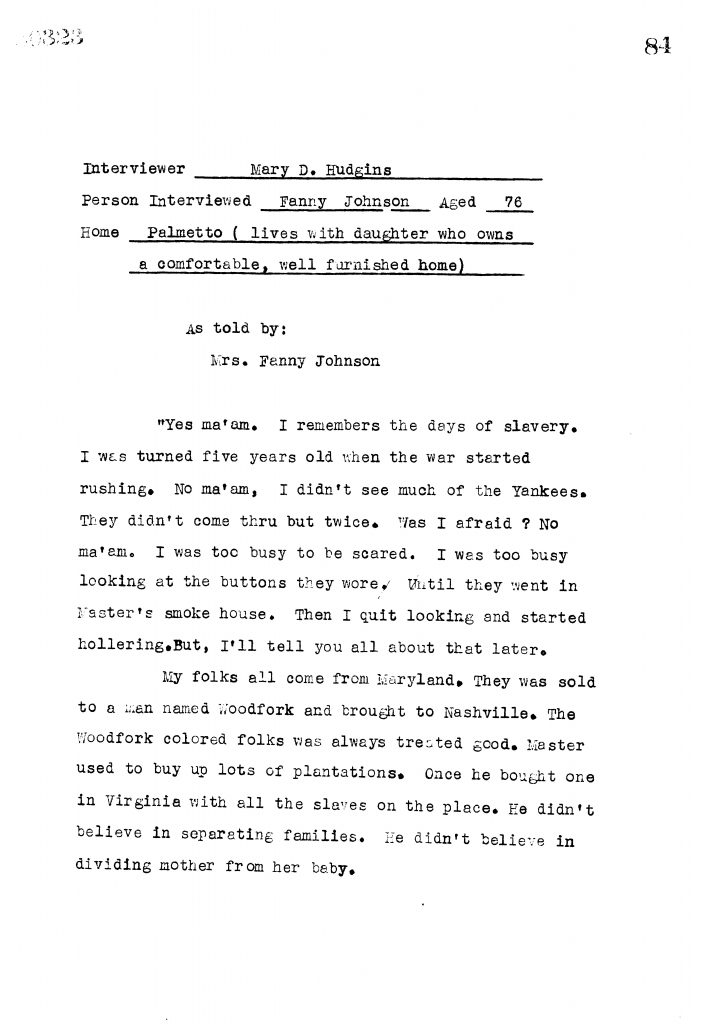

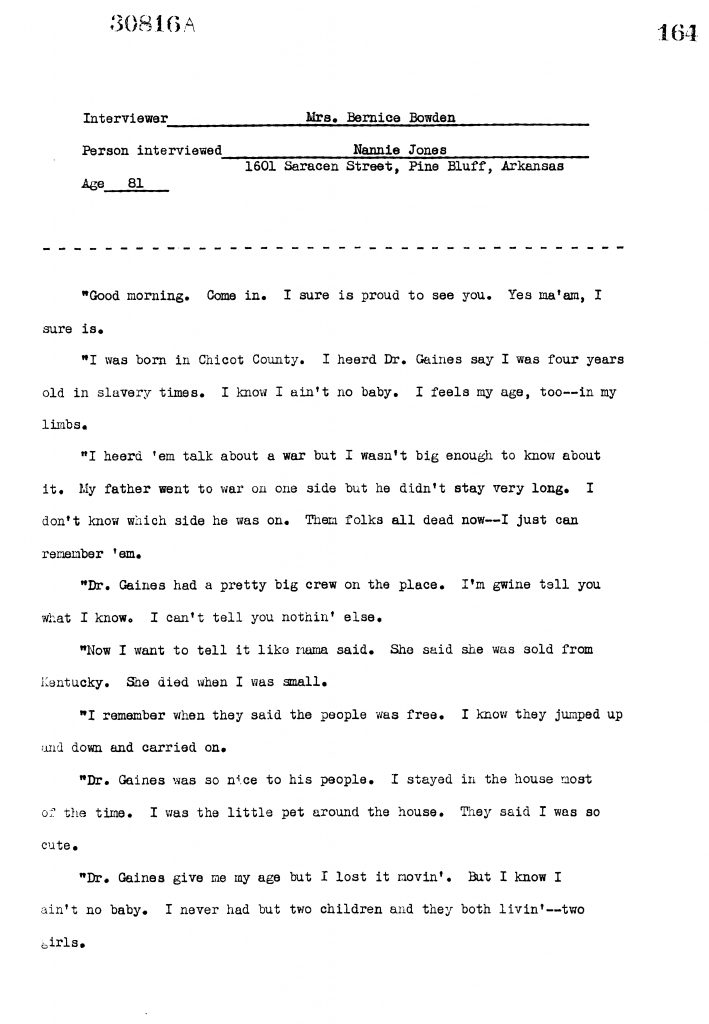

In the first book-length study of Arkansas slavery in more than sixty years, A Weary Land offers a glimpse of enslaved life on the South’s western margins, focusing on the intersections of land use and agriculture within the daily life and work of bonded Black Arkansans. As they cleared trees, cultivated crops, and tended livestock on the southern frontier, Arkansas’s enslaved farmers connected culture and nature, creating their own meanings of space, place, and freedom.

Kelly Houston Jones analyzes how the arrival of enslaved men and women as an imprisoned workforce changed the meaning of Arkansas’s acreage, while their labor transformed its landscape. They made the most of their surroundings despite the brutality and increasing labor demands of the “second slavery”—the increasingly harsh phase of American chattel bondage fueled by cotton cultivation in the Old Southwest. Jones contends that enslaved Arkansans were able to repurpose their experiences with agricultural labor, rural life, and the natural world to craft a sense of freedom rooted in the ability to own land, the power to control their own movement, and the right to use the landscape as they saw fit.

-from University of Georgia Press

Saturday, September 16, 2023

2:30-4:30

Lakeport Plantation Museum

601 Highway 142

Lake Village, AR 71653

2:30 – 3:00 pm — Lakeport Open House

3:00 – 3:45 pm — Presentation by Dr. Kelly Houston Jones

3:45 – 4:30 pm — Book Signing with Dr. Kelly Houston Jones

A Weary Land is $35 each (includes tax).

To guarantee a copy to purchase, please call 870-265-6031 to reserve your copy.

Space is limited.

Please register for this FREE event by calling 870-265-6031 or emailing roloughlin@astate.edu.