Hiram E. Wetherbee Timeline

The Wetherbee House, built around 1873 for Hiram E. and Dora Wetherbee, is the oldest and last remaining home in downtown Greenville. Wetherbee, a Kentucky-born Union Civil War Veteran, returned to the Delta after the Civil War and founded a prosperous hardware store in Greenville. The home was added to the National Register in 1977. Today, it is under renovation to become Wetherbee’s, a retail space.

1842 — Hiram E. Wetherbee is born in Boone County, Kentucky.

1860 — Wetherbee, an 18 years-old farmer, is living in Golconda, IL along the Ohio River. He and six siblings are in the household of his father, T. W. Wetherbee, a wagon maker.

1862, August 16 — Wetherbee enlists at Golconda in 120th Regiment Illinois Infantry Volunteers, Company E as a teamster/wagoner. A younger brother, Wesley O. Wetherbee, joined the 29th Illinois Volunteer Infantry in 1864.

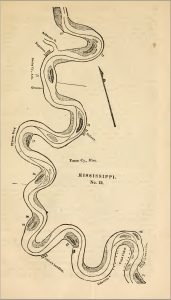

1862-1865 — The 120th IL Infantry transfers to Memphis, Tennessee. The 120th participated in the siege of Vicksburg (May-June 1863) and spent time in Old Greenville.

1865, September 10 — Wetherbee is discharged from the Union Army at Memphis.

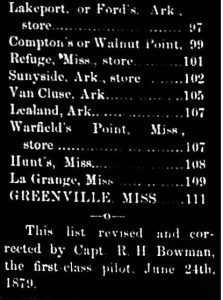

1867-1870 — Wetherbee likely arrives in new Greenville. He initially farmed and worked as a tinsmith. In the 1870 Census, he has $1000 in real estate and $700 in personal property. His neighbor is Samuel Elliot, an Indiana-born hardware dealer who was appointed Greenville’s postmaster in 1868.

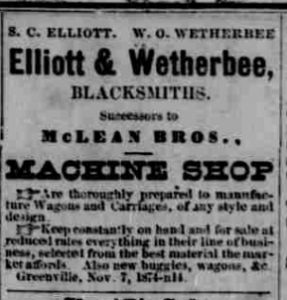

1871 — Wesley O. Wetherbee, Hiram’s younger brother and a Greenville blacksmith, marries Belle V. Elliott.

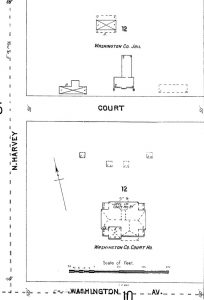

1873 — Wetherbee purchases land from Mrs. Blanton Theoblad, where he would build his home.

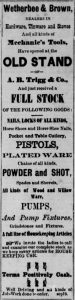

1874, October 3 — Advertisements for Wetherbee & Brown Hardware appear in The Greenville Times. Records suggest the hardware store was located on the now lost Mulberry Street parallel to the Mississippi River. In 1885, the store was relocated to Walnut Street.

1874, October 28 — Wetherbee weds Dora McCoy at Golconda, Illinois. The couple raise three children: Harry Lon (1875), Edna (1877), and Ethel (1895).

1878, September 30— Wesley O. Wetherbee, Hiram’s younger brother and a Greenville blacksmith since at least 1871, dies. His death coincides with the yellow fever epidemic. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

1905 — Wetherbee dies and is buried in the Greenville Cemetery. Wetherbee’s son, Harry, takes over the hardware store.

1911 — Dora Wetherbee dies and is buried in the Greenville Cemetery.

Wesley O. Wetherbee worked as a blacksmith according to this November 4, 1874 advertisement in The Greenville Times

1950 — Wetherbee Hardware Store claims to be the oldest in the state of Mississippi.

1957 — Wetherbee Hardware Store is sold to new owners. It closed in 1966.

1973 — Ethel Wetherbee Finley is the last Wetherbee to live in the home.

1973 — The Council of Greenville Garden Clubs purchases the home. Under an architect’s supervision, the house is restored to its 1870s design and used as a clubhouse and museum.

1977 — The Wetherbee house is added to the National Register “as a rare example of the modest cottage type of domestic architecture common…in the post-Civil War decades” in Greenville. The Wetherbee carriage house is believed to be pre-Civil War.

Note: In addition to the National Register nomination, Mrs. Robert M. Harding’s 1978 article, “The Historic Preservation of the Wetherbee House,” published by the Washington County Historical Society is a good source of information on the Wetherbees and the home. Other sources consulted include U.S. Census records, Greenville Times, Delta Democrat-Times, Hiram Wetherbee’s pension file at the National Archives, among others.